The Business Co-Founder's Dilemma 2012

Most startup ‘business’ co-founders will find a certain kind of problem very familiar. Before I state the problem let me lay down a little groundwork with a neat digression. There is a slightly depressing Japanese saying which says “the nail which sticks out gets hammered down”. You may also know the American saying “The squeaky wheel gets the grease.” There’s an interesting interpretation of these as applied to learning.

Most startup ‘business’ co-founders will find a certain kind of problem very familiar. Before I state the problem let me lay down a little groundwork with a neat digression. There is a slightly depressing Japanese saying which says “the nail which sticks out gets hammered down”. You may also know the American saying “The squeaky wheel gets the grease.” There’s an interesting interpretation of these as applied to learning.

“You should work on your weaknesses to complement your strengths”, and “You should work on your strengths to make up for your weaknesses.” I can see the merits of both schools of thought, but how does one choose between them?

This argument isn’t just a philosophical one. I’m someone who would love to build an internet-based business and disrupt fossilized businesses with innovation and agility! However, since I am a minor nerd with no real programming skills, I run immediately into the classic problem of finding a suitable technical co-founder. If this problem doesn’t put you off, you are left with the choices of:

- paying for development,

- building it yourself, or

- building a valuable skill set like online marketing / growth hacking (jargon, sorry) / Design / SEO that you can then use to persuade a technical co-founder.

Avoid being the business guy who says “I’m great for you because I know X, Y and Z, who we can approach for funding/customers/advice.” If somebody offered to partner me by using a carrot like “mentor advice”, I’d swiftly conjure up some very NSFW language to decline.

I don’t have a definitive answer to what is a complex problem dependent on your relative strengths, and preferences, though by sharing, I hope I can give you an example of what has worked for me.

Option 1 is too expensive for me, so I’m automatically bumped towards options 2 and 3. The common denominator for both is that they involve some serious learning and effort.

The choice between learning programming and grooming myself to be competent in 1 of 4 possible non-coding skills is far from obvious. Even if I could learn to be a passable programmer, would that serve my needs? I might still need someone competent in the skills listed in point 3 (aka what Danielle Morrill of Referly calls distribution hacking).

Learning distribution hacking is a compelling idea. An entire generation of would-be entrepreneurs are scrambling to pick up esoteric skills that can get them a leg up on the facebook-obsessed social-media-agency crowd, and also get heard in a marketplace crowded by corporate giants flexing their financial muscle in Google and Facebook ads. The urgency is palpable. But what are you going to sell if you can’t guarantee yourself a technical co-founder.

Perhaps the right way to go about this is to learn to code first. Learn that, and if you can build your MVP, which in turn can be part of a pitch to a VC, persuade a technical co-founder that you have the tenacity and the brains to realize your vision, or just run with it and keep building. If at some point the need for distribution hacking becomes unavoidable, heck, you’ve built up enough self confidence to give it a go.

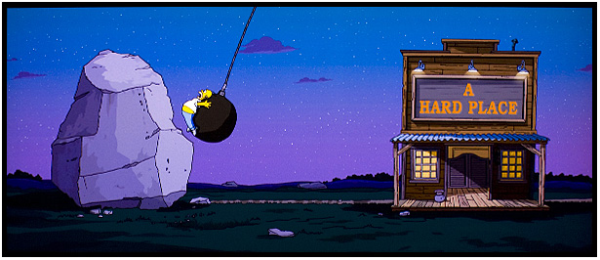

The only possible downside to the plan described is that you could take so long to learn and to build your minimum viable product that the same time could have been used to become a more than competent distribution hacker. Now you are behind schedule, surrounded by capable distribution hackers lapping up the market opportunity you were too slow to defend, and you find yourself still struggling to succeed and with nothing to show for a year’s worth of misery. If you’re a business co-founder who identifies with this story, tweet it and mention me. Who knows? Maybe we can swap brogramming tips.

Tweetcomments powered by Disqus